Testing the boundaries

Photo by Photo by Abby Hanson

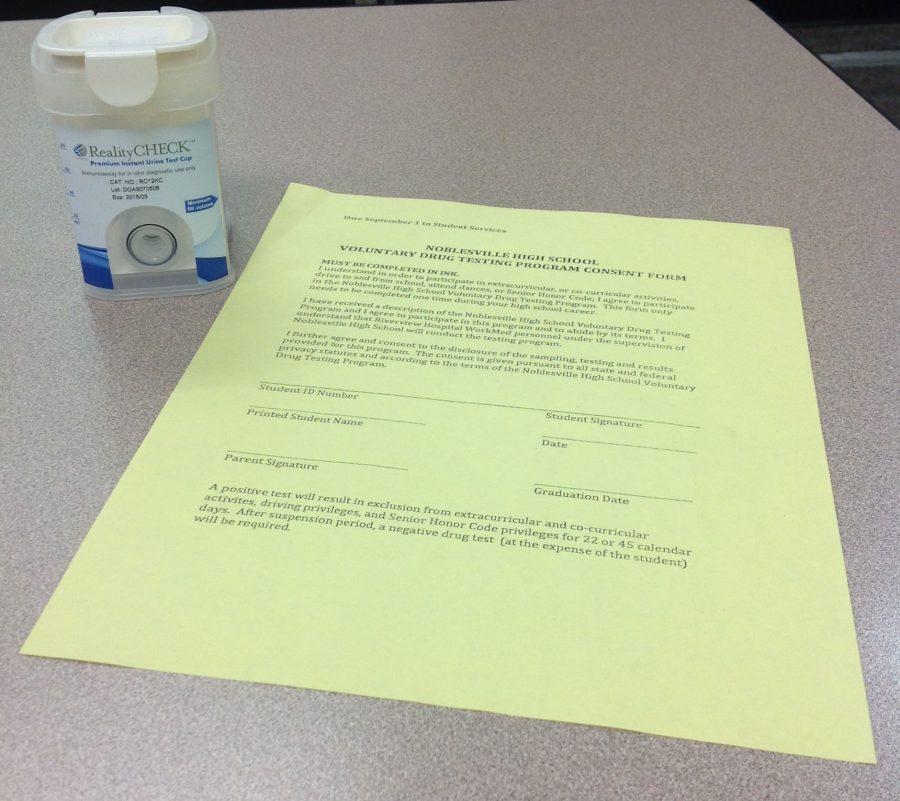

To administer drug tests at NHS, a urine sample is taken from a randomly-selected student. Last year, about 500 students didn’t sign the form consenting to such a test.

August 29, 2016

Meet sophomore Kendra Loos, an everyday high school student. Between choir practice and challenging classes, she juggles hobbies, sports and a social life. She is a straight-A student with no history of disciplinary issues.

But because of a desire to attend one dance at the start of her freshman year, she could be required to urinate in a cup at any given moment for the rest of her high school career.

Loos is not alone. Last year, about 2,400 students were in the testing pool, according to assistant principal Dr. Craig McCaffrey. In order to receive the basic privileges definitive of high school independence like driving to school, attending dances and participating in extracurricular activities, students must sign a form giving their consent to be tested. Random drug testing is not only ineffective; it also strips students of true choice.

Since a 2002 Supreme Court battle, voluntary drug testing of students in extracurriculars has been considered legal. But the vote was only 5-4, with Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg still finding the ruling “Capricious, even perverse.” Why? It borders violations to the fourth and fifth amendments which call for no unlawful search and seizure and protection from self-incrimination. The loophole here lies in one word: voluntary.

Yes, the testing is technically voluntary. Students have a choice. They also have a choice when someone steals and ransoms their beloved cat. Here, they can fork over a payment to get Mr. Mittens back, or they can risk losing him forever. That’s not so much of a choice as it is a lose-lose situation; they’re giving up their money or their pet.

So is the way of “voluntary” drug testing. Here, you’re agreeing to pay the high cost of privacy and constitutional protection in exchange for the basic freedoms you enjoyed in middle school, a decision that you shouldn’t have to make.

The administrators involved in this process aren’t sadistic, tyrannical overlords. They simply want to keep us safe, but perhaps their method of execution is misguided.

“The purpose [of drug testing] is one: it gives students another reason to say no,” McCaffrey said. “Secondly, those that do test positive [are connected] with drug counseling and those kinds of things to help them stop what they’re doing.”

Does this deterrent resonate in the rapid-fire teenage brain? In the eyes of the American Civil Liberties Union, American Academy of Pediatrics and Indiana Prevention Resource Center, no. A statement from IPRC asserted that “We would be better off using methods that have at least some evidence of effectiveness.”

While counseling would be the next logical step in helping students that already have a discovered drug

problem, more emphasis should be placed on preventing this issue from even occurring. Shouldn’t there be more preventative measures than DARE once in 5th grade?

“We don’t release our numbers, but we have very, very, very, very few kids that test positive,” McCaffrey said.

If NHS has so few kids testing positive that it warrants four “very”s, why is it conveying a broad lack of trust and requiring testing of the vast majority? When so few drug problems are discovered by these tests, money that could be better spent on preventative measures is being spent on something with questionable effectiveness.

In the fight against drugs, there is no magical solution, but stripping hundreds of students of their privacy and threatening their constitutional rights isn’t the answer. Random drug testing just doesn’t do the trick; it fails as a deterrent and leaves students either without free will or without a full high school experience. If we devote the money spent on more effective prevention methods, we can better reach a broader student base, no urine samples necessary. When random drug testing is in place, it’s the system, not the student, that fails.