Take a look in a book

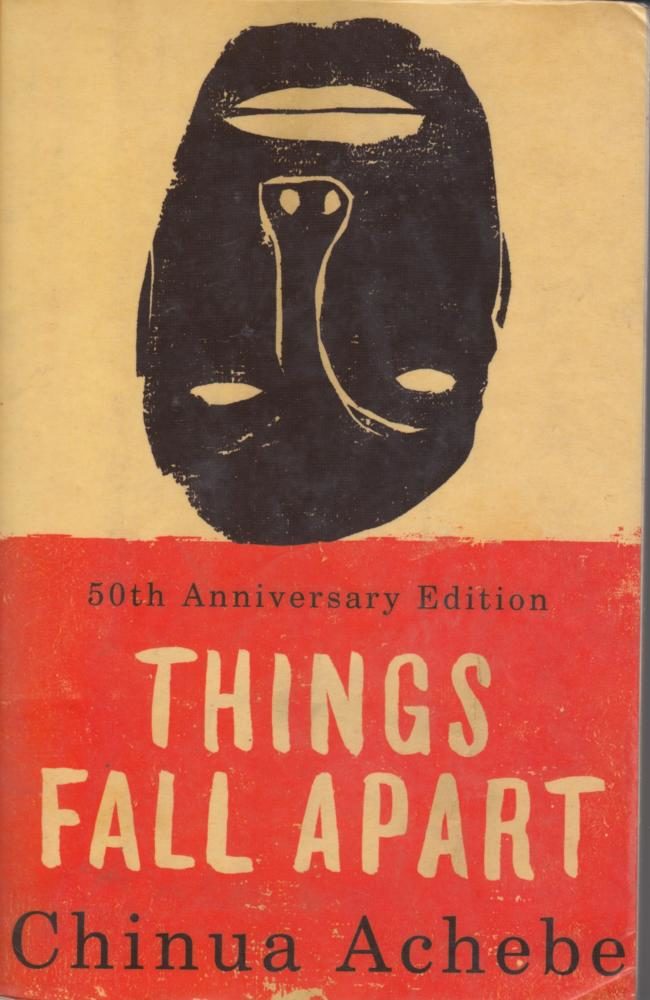

Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart tells the dark story of Okonkwo, a yam farmer in precolonial Nigeria.

May 1, 2017

Mandatory books. Even to the avid reader, they can appear daunting, cryptic or simply boring. But not always. Read on to see reviews by three Mill Stream staffers of NHS-assigned novels Things Fall Apart, To Kill a Mockingbird and The Great Gatsby.

Things Fall Apart

Assigned to: Sophomores

Review by Abby Hanson

We’ve all been there. Our yams aren’t growing well. We have to beat our wives because they don’t make dinner on time. We’re forced by tribal custom to murder our adopted sons. Relatable, right?

While most young people vow at one point or another to approach certain aspects of life differently than their parents, it’s unlikely that such teenage rebellion will morph into a crazy, lifelong obsession of avoiding the weakness of their fathers. In Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart (TFA), the story of Okonkwo, a yam farmer of the Igbo tribe in Nigeria, that’s exactly what happens. As Okonkwo is consumed by cruelty, pride and a need for control, the titular “things” of his life crumble around him, cumulating in a tale of domestic violence, murder and suicide.

Unlike books like Joseph Conrad’s famed Heart of Darkness, Achebe uses TFA to display a different side of precolonial Nigeria, a side that shows African people as, well, people. With many of my classmates having never ventured outside Indiana or Florida, I looked forward to reading a book that would both shed Eurocentric views of literature and expose Noblesville’s sophomores to a world simultaneously inside and outside their own.

Unsurprisingly, TFA’s story of a Nigerian man’s violent midlife crisis, doesn’t resonate well with an audience that less than a year ago obtained the right to drive an automobile. At one point, we were tested over a line of dialogue in the book, and no one in my class realized that it was a sexual innuendo. If the book isn’t understood by any of the students reading it, what’s the point of teaching it?

I enjoy literature because it’s bigger than the events on the page. It’s universal. But to 16-year-olds, Okonkwo’s struggles of pride and redemption don’t make sense at this point in their lives. Add a culture we know little about and projects that don’t help us understand the symbols or meaning of the novel, and we might as well have read a three-paragraph Spark Notes version.

***

To Kill a Mockingbird

Assigned to: Freshman

Review by Brianna Lopez

To Kill a Mockingbird. Just a glance at the title makes me nostalgic for the times when reading books in English was fun. To Kill a Mockingbird had it all. Memorable characters. Humor. Despair. An enticing plot. Mystery. Atticus Finch. Is it possible to read To Kill a Mockingbird and to not wish, at least a little bit, that Atticus was your dad?

There are so many reasons why this book is a classic and a favorite of many. The characters, Scout, Jem, Dill, Atticus, Boo, and so many more are so enthralling. The plot of the story masterfully entwines the deep and complex themes of ignorance and prejudice with the exciting adventures of Scout’s youth. The book is so adept at making the reader laugh, scream in rage, or weep. Also, it isn’t boring, like countless other books that have been forced upon English students (*cough* Things Fall Apart *cough*).

However, To Kill A Mockingbird made a particular impact on me because of how powerful the writing and the argument is, even today. For a book that was written in 1960, it remains relatable to kids today. The story simultaneously entertains the reader and expresses a moral lesson. Lee’s argument about the dangers of prejudice and racism, as seen in Atticus’s court case, are made accessible because they are mirrored in Scout’s encounters with Boo Radley. Scout learns that, as Atticus wisely sums up, “You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view … until you climb into his skin and walk around in it.” Scout’s childhood whims also make her recognizable to kids today, even though she exists in a world unrecognizable to many kids today: a world defined in history by racism and segregation.

To Kill a Mockingbird is brilliant because it simplifies, yet strengthens the argument against prejudice, making the argument effective to people of all ages, and of all generations. The simplicity of the anecdote is more effective than any impersonal statistic or logical essay could be. That is why this book is so important; it is an enduring argument against hate and intolerance in a world that has not eradicated these problems. It proved that a writer can have an amazing impact on people, even 57 years later, and that is pretty magical.

***

The Great Gatsby

Assigned to: Sophomores

Review by Eli Maxwell

Imagine leaving the midwest and moving somewhere else. The Big Apple. Next to your new home is an extravagant mansion. Each week your neighbor, who has not yet introduced himself to you, throws wild parties populated with beautiful people.

The Great Gatsby, by F. Scott Fitzgerald, takes place in New York City, 1922. Throughout the novel’s near 200 pages, you meet a variety of characters from many different backgrounds who are all unlikeable for a variety of reasons. First, there is Daisy Buchanan, an extremely wealthy woman from Kentucky who has never worked a day in her life. She has an unearned sense of entitlement, a lack of empathy and no ability to make difficult decisions, no matter how important they are.

Then there is Jay Gatsby, the man whose only objective in life is to reunite with Daisy, the girl he dated for a month five years ago and who is now married to a rich bore. Gatsby earned his money through bootlegging and through illicit activities. Gatsby is under the impression that if he gets the thing he wants— that “thing” being an actual human being— he can be happy again. The technical term for that is “objectification,” thus revealing the reasons for Gatsby’s dislikable identity.

What some people don’t understand is that you aren’t supposed to like these characters. In fact, you’re supposed to dislike these characters. Too often, readers determine the value of a novel based on the likability of the characters. The point of The Great Gatsby is not to fall in love with the characters, it’s to see their flaws.

The Great Gatsby is considered a classic because of the way it portrays the American Dream. Gatsby is a man who did not come from wealth but who eventually becomes wealthy, a concept that America was founded on. Fitzgerald portrays the American dream as somewhat of a lie in this novel. He associates wealth with corruption and gold with death.

John Green, host of YouTube series Crash Course English Literature, said, “Wealth was the American dream. But the foul dust that trailed in the wake of those dreams— the casual destruction, the cyclical violence, the erosion of altruism- make it clear that, at least to Fitzgerald, wealth isn’t simply good.”

The point of The Great Gatsby is not to glorify the lifestyles that the characters live or to make readers want to be like the wealthy Jay Gatsby. Fitzgerald wrote Gatsby to show that wealth is not always worth it in the end. After 92 years, some people still don’t get it.